The SFFaudio Podcast #459 – Jesse, Paul Weimer, Bryan Alexander, and Julie Davis talk about The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton

The SFFaudio Podcast #459 – Jesse, Paul Weimer, Bryan Alexander, and Julie Davis talk about The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton

Talked about on today’s show:

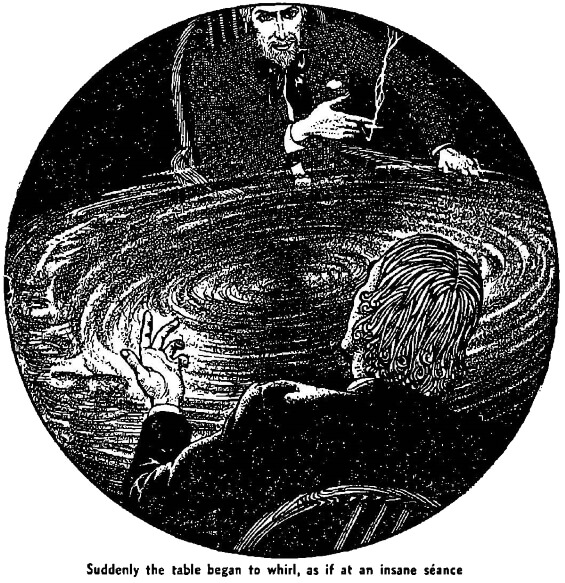

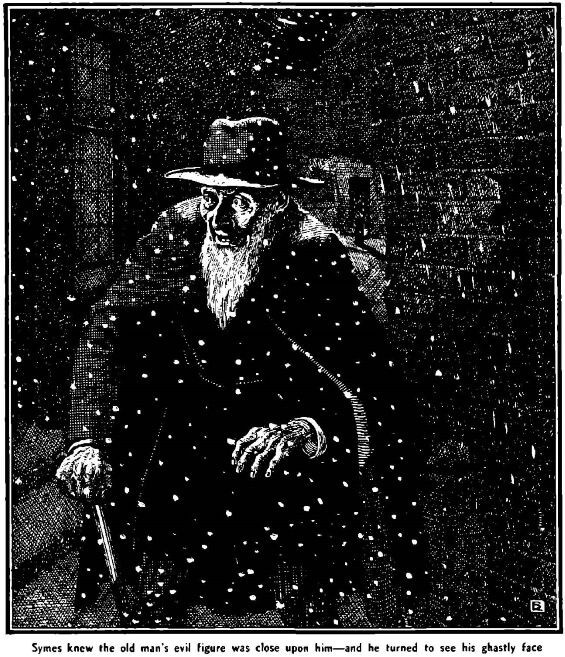

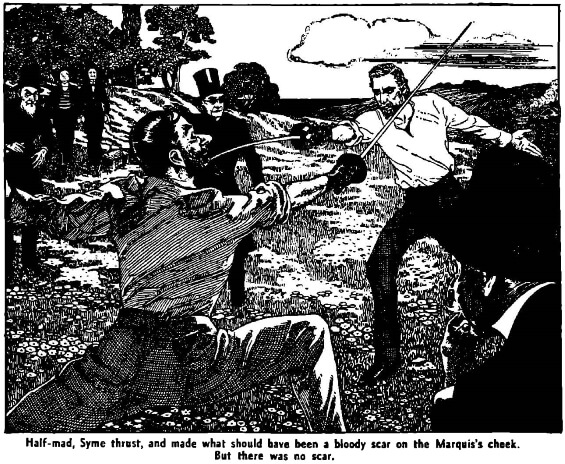

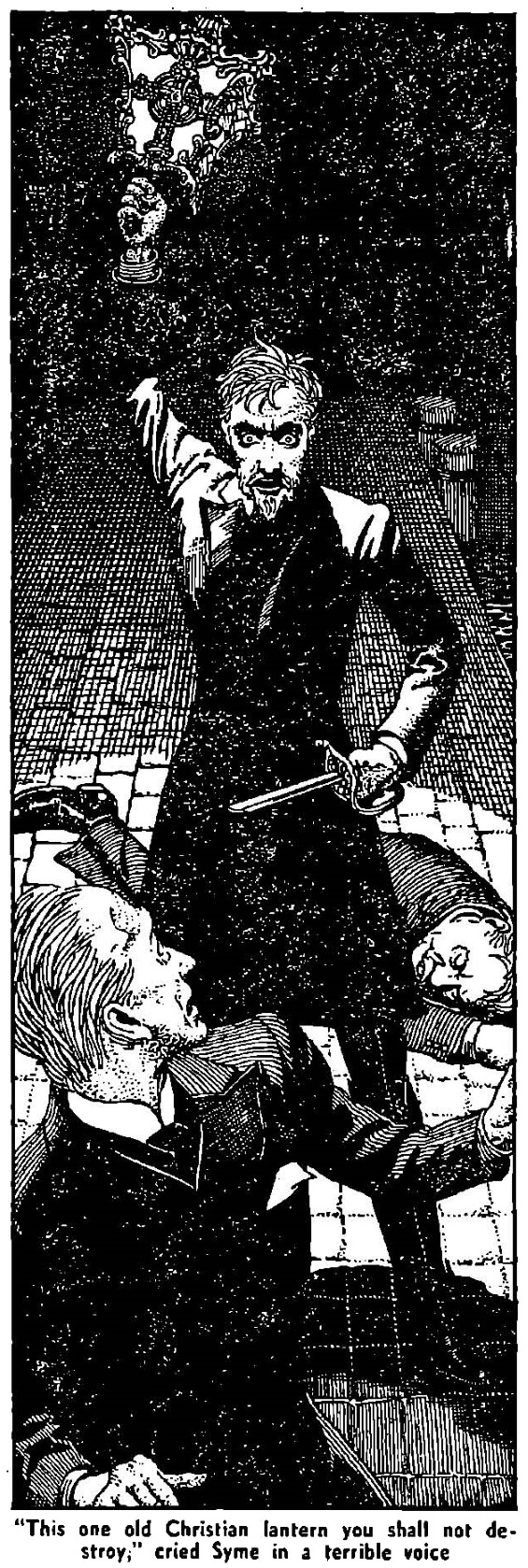

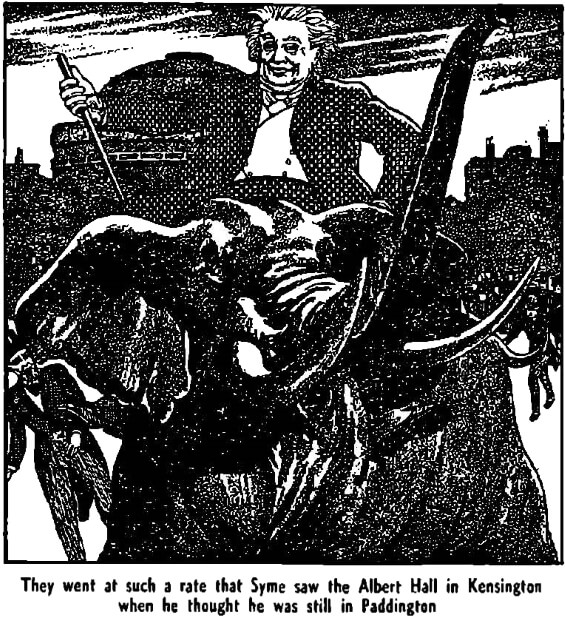

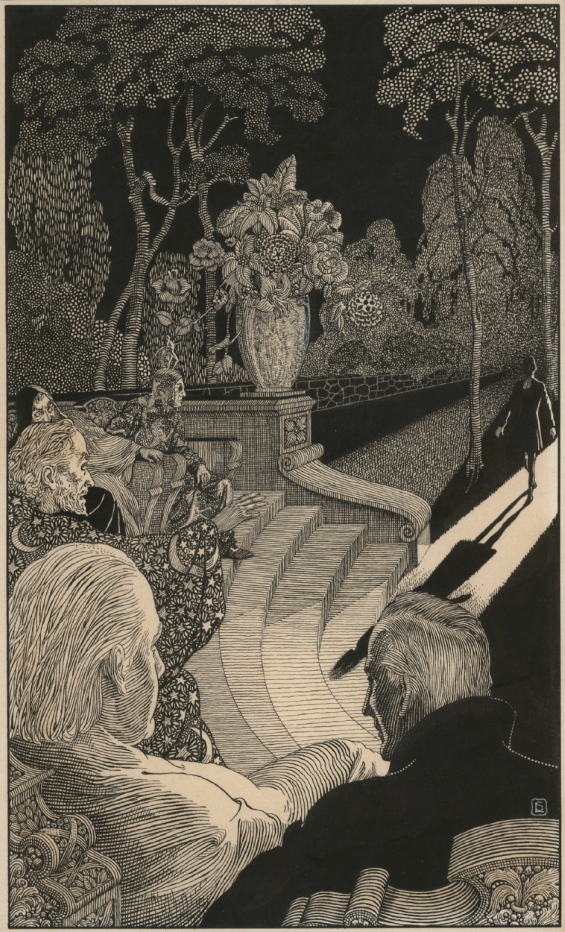

1908, subverting expectations, thriller philosophical novel adventure fantasy, a book about anarchists (not really), hot topic, pre-WWI, bring down the system, everybody is a dynamiter, Michael Collins, if you don’t seem to be hiding nobody hunted you out, anarchy against anarchy, the Orson Welles adaption, easier to understand, one female character in the book and she shows up on the last page, Mercury Theater, Welles as Sunday, evil or good?, wine commercials, this old fat guy talking about wine, large people refracted through later media, Gilbert in The Sandman is G.K. Chesterton, confession, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, because it has detectives in it?, sudden reveals, that person is not an anarchist either, the same trick over and over, the Professor, the Marquis, the Father Brown mysteries, Miss Marpole, Reading Short and Deep, The Angry Street: A Bad Dream by G.K. Chesterton, like Scrooge, a very interesting guy, a very rare bird, a conservative intellectual, explaining a lot of what’s going on, The Tremendous Adventures Of Major Brown, The Game (1997), sympathetic to anarchism, the ISIS of its day, submitting to ISIS, its not a critique of anarchism at all, a caricature of anarchists as terrorists, non-violent anarchism, a classic problem, non-terroristic anarchism, fantastic turns of phrase, lampshaded, lighting a lamp against the darkness, a fun romp, the reality of police going after subversive groups, it’s about God, and your relationship to Him and yourself on Earth, Chesterton’s fence, an axiom, a principle, completely reasonable, why conservationism should be the default, he’s so persuasive and witty, these are the kinds of conservatives Jesse is afraid of, the Catholic in Julie, the wisdom of the ages, a noble ideal, Terry Pratchett, Mark Twain, Neil Gaiman, “a man who really knew what was going on”, he dresses kind of goth-y, carrying a sword-cane, the people he admired carried sword-canes, Alexander Pope, The Dunciad, a dog named Bounce, Dante’s Inferno, a great age of satire, turning things upside down, laughing, I love lists, a poet who loves lists, arch-humour, that young man, wild white hat, a cause of philosophy in others, a preview of the ending, Scott couldn’t stand this book, Julie was enchanted by it, its unfixed, there’s no grounding, the duel scene, removing parts of his body, he’s a robot, he’s disassembling himself, a little too far?, Scott is a writer, writers reviewing fiction books, how it was constructed, the subtitle: “A Nightmare”, this is a fantasy, this is a fantastic village, this isn’t real, Dante’s Paradisio, this is just allegorical, that’s hilarious, Scott was raised Catholic, Julie (like Chesterton) was a convert, going all the way, a different kind of reader, the cosmos had turned upside down, looking at everything from the back, where the book’s theme is made manifest, this is what I mean, The Everlasting Man, H.G. Wells, proof, a little dig on evolution, shaking the reader, you have no firm fixed ground, wherever you land you’ll find God, “They said my very walk was respectable, and that seen from behind I looked like the British Constitution”, ridiculous, the conservative view, not a poet who is a poet, the common working man, no peasant wants anarchy, every millionaire is at heart an anarchist, plutocrats as anarchists, WTO protests, agent provocateurs, during the Black Panther era, policeman in disguise: let’s blow stuff up, energetic FBI contributions, kind of Philip K. Dickian, a completely different reveal, A Scanner Darkly, Bob Arctor, Robert Downey, Jr., did Philip K. Dick read this book?, Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?‘s fake police station, is Sunday Jesus Christ?, Sunday is God, dressed in the disguise that reveal them as who they really are, pantheists, when men wake up, beautiful nature, a garden, the unmasking, the garden may be Gethsemane, 33 pieces of paper of no value, the question of betrayal, of all days of the week, Rosamund, at the end of time, Heaven is somewhere in Normandy, the marchers, what’s going on?, they all admit they have one hope, the man in the Black Chamber, such a conservative fantasy, secret policeman, the trailer for the 2016 movie adaptation, Nazis and fascists, how could you do a straight up adaptation of this?, Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula: 1895: Seven Days In Mayhem, Dracula marries Queen Victoria, anarchists against Dracula and the vampire elite, a concentration camp holding Sherlock Holmes, Gilbert and Sullivan, a weird detective story about soap operas, the way Sunday is depicted, some of the ways that Sunday is described, he swooned, Sunday is both the Devil and God, looking at him from his hind-parts, kinda weird, the pure good thing, many out loud laughs, “He came of a family of cranks, in which all the oldest people had all the newest notions. One of his uncles always walked about without a hat, and another had made an unsuccessful attempt to walk about with a hat and nothing else.”, his turns of phrase, why Chesterton is loved by Gaiman and Pratchett, the same kind of wry comedians, easy to get along with, shall we go out and have dinner together now?, isolation, twice two is 2,000 times one, George Bernard Shaw, ‘too see you’d think Britian was in a famine – to see you you’d think we’d know why’, fun and dangerous, WWI, a white feather, The Four Feathers, wearing their white feathers proudly, making another joke about being fat, “anarchists!”, what does that have to do with… Bryan?, Gavrilo Princip was not an anarchists (he was a Nationalist) but he was called one, anticipation of WWI, a glimpse of the desire for violence, Teddy Roosevelt, the older detective, detecting pessimists, discovering a crime in a book of sonnets, really funny, Charles Stross’ laundry series, surveillance and data analysis for pre-crime, chilling, why he’s a dangerous guy, defending the indefensible, he spells it out so clearly, do we all know what’s going on here, the book starts with a poem, looking at it in sentences,

“A cloud was on the mind of men

And wailing went the weather,

Yea, a sick cloud upon the soul

When we were boys together.

Science announced nonentity

And art admired decay;

The world was old and ended:

But you and I were gay;

he’s conflating nihilism and decadence and decay with anarchism, The Decline Of The West, The War Of The Worlds, a grim vitality, “what do you want? martyrs!”, written as a cure for melancholy, An Anatomy Of Melancholy, reading melancholic writers, lassitude, making you thoughtful, flashy, so light in its stated topic, if this was written today…, Britain’s who travel to the Middle East to join ISIS, a pacifist book, pro-life, imagining the bomb going off, the value of each human life, Isaac Asimov, violence as the last refuge of the incompetent, chances, who is the man in the black room?, he’s the Alpha and the Omega, in Syria the war is winding down, a 90% decrease in violence, why did the Vietnam War happen, big agents doing things, why does this anarchist council exist?, I can’t believe that any common man would support, a certain class of people thought it would be honourable or profitable, a different subject for the book, a secret agent style version of this book, Moriarty, Fu Manchu, the daughter of the Dragon, a boogeyman, Fu Manchu is trying to overthrow the British occupation of China, a sympathy argument for Fu Manchu, Pan-Asia, Genghis Khan, turnabout is fairplay, pot kettle black, Alan Moore’s The League Of Extraordinary Gentleman, Captain Nemo, his mother was a hardcore Stalinist, she was convinced Stalin the great hero of the 20th century, Dorothy Day, attacking organized religion, Marx, neither god nor master, a coherent argument to make, James Dean or Marlon Brando, Kryten in Red Dwarf, mere willingness is the final test, a lengthy lecture on the history of anarchism, Mary Woolstencraft’s husband, Things As They Are; Or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, Parents And Children aka Fathers And Sons, what’s more useful a painting or a pair of shoes, a near contemporary, an active Russian thing, Dan Schwent, really different, almost not a novel, it is a dream, nightmare, The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan, that moment, that vertiginous moment, deciding to go another way, setting up these moments, as participators or adaptors, a bunch of people who are wrong about everything, a council, there’s no predominant day of the week, I have to do a podcast on Sunday, it needs to be scheduled, the Club Of Queer Trades stories, how does the schedule happen?, Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman was inspired by G.K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon Of Notting Hill,

“a novel written by G. K. Chesterton in 1904, set in a nearly unchanged London in 1984.

Although the novel is set in the future, it is, in effect, set in an alternative reality of Chesterton’s own period, with no advances in technology or changes in the class system or attitudes. It postulates an impersonal government, not described in any detail, but apparently content to operate through a figurehead king, randomly chosen.”

not really science fiction, radical!, not a fan of revolutions, loving Americans, one conservative to think about, The French Revolution, The Russian Revolution, The American Revolution, Queen Elizabeth II is on my money, Tories fled to Canada, Oliver Wiswell by Kenneth Roberts, the Tories (political party), Canada’s history as a defense against American radicalism, a distorted perspective, Jesse ruined it, not the first nor the last time, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, prime ministers are not that important, the Premier of British Columbia is John Horgan.

Posted by Jesse Willis

The Horla

The Horla

A Piece Of String (aka A Piece Of Yarn)

A Piece Of String (aka A Piece Of Yarn)