Music for the series was composed by Bernard Herrmann, Jerry Goldsmith, Amerigo Moreno, Ray Noble and Leith Stevens. Other writers adapted to the series included Robert A. Heinlein, Sinclair Lewis, H.L. Mencken, Edgar Allan Poe, Frederik Pohl, James Thurber, Mark Twain and Thomas Wolfe. According to Bill Hollweg the two MP3 files have been “cleaned and the volume normalized” – and they do sound great!

Most interesting to me, however, is some of the commentary about this adaptation. On the back of the Pelican Records LP (LP-2013) edition there is critical essay on Huxley, Brave New World and this adaptation, by none other than Ray Bradbury! It is truly wonderful and I have reproduced it below:

There is science fiction and science fiction. There is science fiction still looked down upon by many intellectuals in our society, because it is written by the wrong people. And there is science fiction minus the label, written over in the main stream by acceptable A-1 main-line writers which is OK. And at the head of the list for some 40 years or more you would have to put Aldous Huxley and Brave New World. Whenever lists are drawn up for schools containing the acceptable authors who dare to be imaginative, it is Huxley and Orwell, ten to one.

Forget about Asimov, Clarke, Sturgeon, Heinlein, get lost.

There are a number of reasons beyond snobbishness of course. Huxley was in mid-career when he veered over into Future Country. Behind him lay half a dozen novels, most of which had good or fine reviews, and most of which are still selling moderately well and being read today. But mention Huxley and most people will name the one they know him by, Brave New World.

At the time it was published, much of the novel was fresh and innovative, properly cynical about human behavior and, at times, verging on territory laid out by Evelyn Waugh. Later on, Huxley and Waugh would indeed meet in the middle of the same cemetery. Huxley to dig graves and plant Hollywood types with his After Many A Summer Dies The Swan and Waugh with his The Loved One another shake of similar bones.

Since its publication, Brave New World has been skinned and boned and borrowed from by dozens of less competent writers who saw the serious fun Huxley had with his story and couldn’t resist imitating it.

As a satire today, reread when some of the things it talked about have moved straight on into our lives, the novel suffers as indeed it did back in 1932, from being a half-job. All the good stuff is up front in the book. Toward the end the fun and the imagination of Huxley diminish. Having the Indian hang himself seemed to me, even when I was younger, a bad solution to a good novel. Even Huxley, in 1952 when I first met him, expressed some doubt about his original ending.

But on his way to the finale, let’s face it, Huxley was the only referee we had for our impeding technological game. With foresight and precision he saw the Pill coming and ducked. He circled round cloning long before it became a tv Tale show mini-debate by mini-minds pretending to offer, as a result to most of us, mini-news. The drug culture of today noon occupied Huxley’s mind at breakfast 45 years back, long before he sprinkled mescaline on his Wheaties. While he was at it, old Aldous invented and reinvented the machined pornographies that have infiltrated our cinemas to slumber us better than Nembutal and bore us more than family picnics, well beyond 1984. And if we have not as yet birthed his ‘feelies’ into our world, we are on the thin dumb rim of doing so.

If there is a zero for failure to imagine at the center of the novel, and this radio play, it is the inability of Huxley (and Orwell, too later on) to in any way recognize or prophesy Space Travel. This may well be because of the time we lived in, then, when the Space Age seemed so remote, so impossible, that it could not be entered on any imaginary ledger to tip the scales toward an equally improbable better if not happy ending.

This was revealed in a lecture which I shared with Huxley onstage at UCLA some time in the early Sixties. Speaking first, he wondered again and again, what the next great development in literature might be.

I was stunned. In sat in my chair hardly daring to rise and deliver my speech, for suddenly my evening had changed. I had intended to make a few remarks about why I wrote what I wrote, but suddenly here was Huxley asking and not answering what was, to me, anyway, an obvious question with an obvious answer. What would the next great literature be?

Science Fiction! I wanted to shout. Good Grief and Jumping Jehoshaphat! Science Fiction!

Since every problem you can name in our time has to do with science and technology (name one that doesn’t) what else us there to write about except Pills, technological drugs, automobiles, smog, nuclear power, solar energy, space travel, tv, radio, transistors, free-ways, all, all of them scientific extensions of scientific dreams.

I rose and did not shout it. But I rose and said it, quietly, out of deference to my author hero.

Huxley shook my hand after the lecture and smiled at me with that dry quiet smile of his, and we spoke of Space Travel and how it might have changed Brave New World if he had thought to consider it in the full.

I still wish today that I might take his ghost to Cape Canaveral and whisk him to the top of the Vehicle Assembly Building where I have gone to stare down, with a wildly beating heart at the topmost part of the Apollo rockets lying ready below to give us alternative futures. We are not doomed to stay on Earth and share Huxley’s Indian suicide or Orwell’s Big Brother. When the time is ripe, we will just up and ‘go’.

All this said, when we return to the radio show, here captured to remind us once more that CBS, of all the radio networks, was the most open, the most adventurous, the most creative. Considering the year it was broadcast, 1956, long before Playboy made its real impact on our country, it is a fascinating work, of much imagination and good taste.

Let me step aside now, I have shouted my quiet shout. The next voice you’ll hear, a lovely gentleman’s voice, is that of Aldous Huxley. Would that he were alive today, for anther teatime chat and another long look into a sometimes dubious, sometimes exhilarating Future.

Ray Bradbury

Los Angeles

May 16, 1979

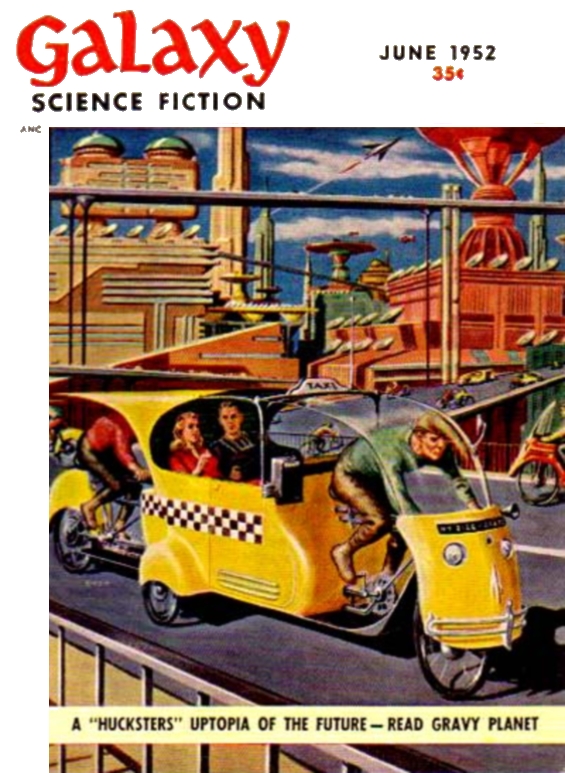

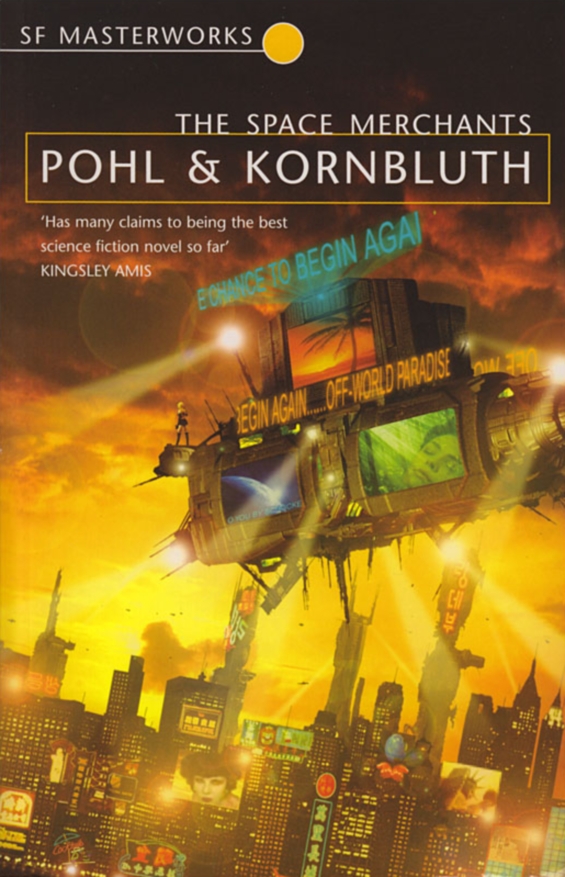

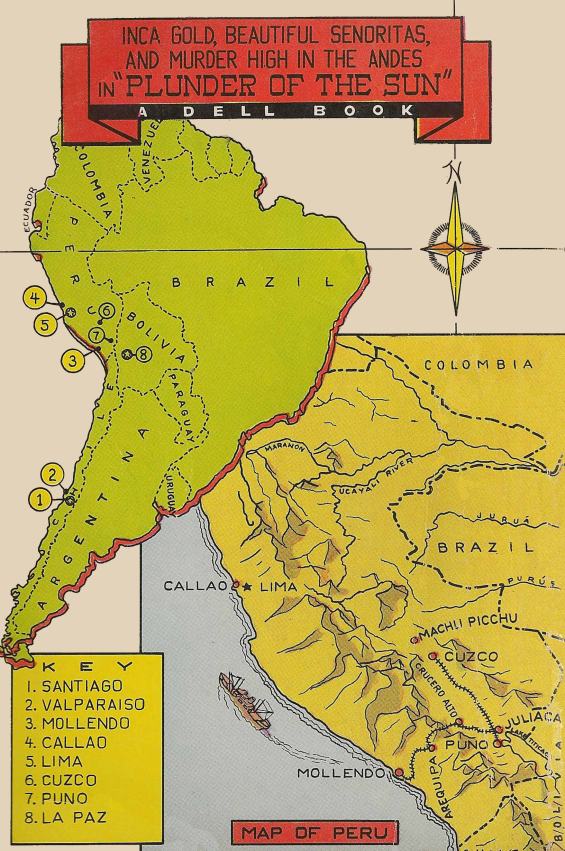

CBS Radio Workshop – The Space Merchants

CBS Radio Workshop – The Space Merchants

No Highway In The Sky

No Highway In The Sky